Malte Jansen, University of Sussex

Wind and solar are the world’s fastest growing energy sources and together generated 12% of global electricity in 2023. The amount of energy produced by wind and solar is expected to increase and accelerate.

Wind generated 1 terawatt (TW) for the first time in 2023 – nearly as much as the total installed energy capacity of the US (1.2 TW). Solar broke this threshold in 2022.

So why in the first global stocktake of the world’s progress towards limiting warming to 1.5°C did the UN say we’re still not phasing out fossil fuels fast enough?

Asia’s economic growth powered by coal

Despite the rapid growth of renewable energy, the most carbon-intensive forms of electricity generation, using coal and natural gas, have risen by 22% and 37% since 2010, respectively. Coal and gas power generation is still the backbone of global energy systems and these fuels are likely to remain dominant for decades to come. Nonetheless, the phase-out of coal (arguably the dirtiest of fossil fuels) is gaining momentum.

During the past decade, the number of new coal power plants built each year has fallen fast. Global coal demand has continued to fall even as the war in Ukraine strained gas supplies.

In the most prosperous OECD countries (or Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), virtually no new coal plants are planned or being built, though new coal mines are still being approved. This is a result of national policies such as the UK’s decision to ban coal in power generation from October 2024.

The US has retired many ageing coal plants since the mid-2010s due to the low price of shale gas. The country’s coal fleet will continue to shrink as 99% of coal projects are more expensive than new clean energy, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

Rawpixel.com/Shutterstock

This picture is very different in Asia. Here, countries have relied heavily on cheap coal to fuel their economies. This is particularly true in China. After adding 27 gigawatts (GW) from coal in 2022 alone, China by itself is offsetting the retirement of coal plants elsewhere in the world.

But there are some signs this is changing. The global pipeline for new coal power plants is smaller than ever and China and India both pledged to “phase down coal” in 2021 at the Glasgow climate summit.

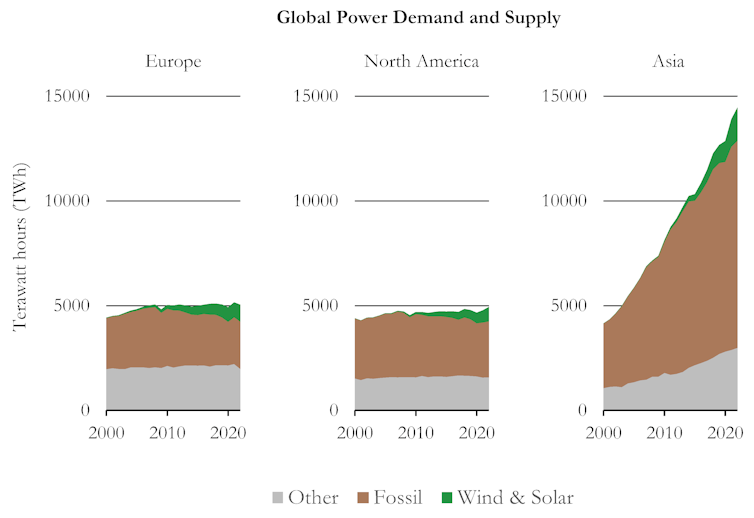

So, rapidly increasing renewable energy hasn’t cut coal and gas consumption at the same rate because humankind is using a lot more electricity than we used to, especially in Asia. In the last 20 years, the use of electricity in Europe and North America has remained largely constant.

Here, renewable energy has slowly eaten into the proportion of energy generated by fossil fuels, while all other energy sources (nuclear, hydro, biomass) have remained about the same. In Asia, electricity demand has tripled since the 2000s, with the bulk of this energy coming from fossil fuels.

Ember, CC BY-SA

Wind and solar are replacing coal and gas

Western economies have made progress in replacing fossil fuels (and coal in particular) with renewables during the last decade. In Europe and North America, wind has become a vital energy source during the winter months when energy demand peaks. And when the wind isn’t blowing, gas generation fills the gaps.

Solar energy, when combined with batteries which can store excess electricity, is also proving to be a cheaper option than both gas and coal in certain parts of the world. In Australia, the industry association Australian Clean Energy Council found that solar panels and batteries are 30% cheaper than gas power plants during peak demand periods.

A Bloomberg NEF investigation found that batteries alone are already cheaper than gas power plants during these times. In fact, solar panels may be generating electricity more cheaply than the grid in some cases.

In India, the cost of generating electricity from solar and storing it in batteries to use during high demand hours has lower costs than existing coal plants. Combined solar and battery plants can activate during peak hours and turn off again when demand drops, regardless of whether the wind is blowing or the sun shining.

In the US, almost half of new energy projects waiting to connect to the grid combine solar and wind with storage technologies, allowing renewables to produce electricity on demand regardless of the weather.

Energy demand is outpacing wind and solar

Wind and solar has only slowed the rise in fossil fuel burning. This is particularly true for China, India, Thailand and Vietnam. These economies have grown rapidly and so has their power demand.

The replacement with renewables in developed economies is too slow to offset this increase on a global scale. Cooling economic activity in Asia – especially China – might reverse this trend, making a replacement pattern similar to Europe and North America feasible.

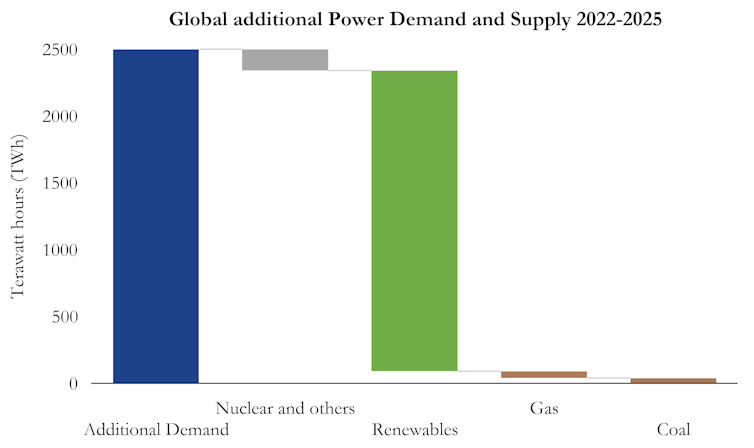

International Energy Agency (IEA)/Malte Jansen, CC BY

While the warnings in the UN’s stocktake should be heeded, the outlook is not entirely gloomy. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) in a report from December 2022, virtually all new demand between now and 2025 will be satisfied by renewable energy. Wind and solar are expected to supply the bulk of this additional electricity, owing to their low cost and high availability.

With new wind and solar now cheaper than existing fossil fuel generation, it is only a matter of time before they fully replace all new energy demand first, and replace existing fossil fuels after – even in fast-growing economies. However, as the UN report shows, this process needs to be significantly sped up to avert catastrophic warming.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Malte Jansen, Lecturer in Energy and Sustainability, University of Sussex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.